In these days of great sadness for what is happening in Ukraine, hope shines through the strength of empathy and solidarity, which crosses borders and reaches right into the heart of war. Romania, where I currently live, is the main gateway for refugees from Ukraine to Europe, as is Poland. From this observation point I went in search of touches of humanity and found many. I am convinced that as expats we have a duty to recount what is happening in the countries where we live. Interpreting reality from a new perspective can be very helpful.

For those born and raised in Western Europe in the second half of the twentieth century, war has always felt distant. Distant in time, fought between the pages of history books or in the stories of grandparents, or distant in space, even if, in fact, it was not. Just think of the example of Yugoslavia. But we liked to think about war this way: unfair, cruel, terrible, but “belonging to others”.

Perhaps it was a kind of defence mechanism, a way of not being overwhelmed by horror. Maybe we should be a little indulgent to ourselves for every time we were not emotionally involved in other wars. Now I realize how superficial we were, and how bitter the awakening is today.

During my years in Bucharest, I often heard sirens, but was only afraid the first time. I often saw fighter planes pass over my house, but they didn’t worry me: Oh yes, there are NATO bases, I said to myself.

Today, however, war is close and is invisibly but tenaciously creeping into everyone’s daily lives. In recent days Italy has sent more planes the Mihail Kogalniceanu military base, near Constanța. Yet Constanța always evoked sea rather than war for Romanians, and for me, until a week ago.

A friend sends me a message: you can donate blood for wounded Ukrainians at the blood transfusion center at the Central Military Emergency University Hospital. I am overcome by anxiety and hearing my children in the next room going on with their life does not make me feel better. I need to go out. Passing near the Ukrainian Embassy is painful: flowers, candles, signs in many languages. A group of a dozen people are out there, maybe waiting to enter, maybe waiting for news. I dare not ask; I dare not get close to those harrowed eyes.

I need to find some humanity in these cold days, to get, if not relief, at least a moment of respite in my thoughts. I want to listen and talk about the solidarity that runs along those 600 kilometers of border with Ukraine, and that from there engulfs the whole of Romania. After all, Halso made up of the many gestures of ordinary people and organizations, and this, too, must be told.

My friend Alexandra Paucescu shows me the photos of the Caradja Cantacuzino Association, one of the many organisations receiving aid in Bucharest: the number of volunteers and the amount of essential goods is impressive. Meanwhile, within a few hours, the entrepreneur Alexandru Panait created the refugees.ro platform, to connect Ukrainian refugees, who can specify their needs, with those who want to help them with housing, lifts, meals, and basic needs. And the number of those who help out continues to grow, as well as the list of restaurants and hotels that offer meals and accommodation to Ukrainian passport holders.

Refugees form Ukraine arriving at Isaccea (Romania). Photo © Mugur Varzariu

As I scroll through the endless offers of help online, with hundreds of Romanians opening the doors of their homes, welcoming people to their table, or giving lifts, I get a message from Simona Carobene, an Italian social worker in Romania, who has travelled to the border with Ukraine.

She tells me about the cold, the snow and the many, many people who arrive having covered miles on foot. On her journey, she was left speechless when she received a call from a desperate woman in tears who asked for bulletproof jackets, helmets, gloves and boots for the soldiers.

Roman, a Ukrainian who managed to enter Romania with his wife and five children, could have moved on elsewhere. He has a network of contacts in other European countries, but he decided to stay there, at the border: he speaks English and Romanian; he can help his people. He lives in a shelter with 57 others, many of them children. And he knows that what they need is not only blankets or food, but also not to feel alone. They need a smile, a hug. ‘What hope do you have for your country, for your people?’ asks Simona. Roman shrugs: ‘Eternal life, perhaps’.

Right after this I get a call from Don Valeriano, a priest friend. He’s 50 kilometres from Budapest, on his way back from Italy. Two nights ago, he received a phone call from Lviv: You have to rescue disabled people, it is difficult to keep them in the improvised bunker in the building where they live. Valeriano and a colleague take a car and a bus and leave.

They arrive in the middle of the night at a secondary custom, hoping it will be easier for them to pass. And so it is: only three hours of waiting and a dozen people, including two in wheelchairs, cross into Romania. They drive through Italy. . As I write, Valeriano is making another journey, this time to rescue 44 people, mothers and children. Not all minors have documents, but he is confident that also this time there won’t be any problem.

Meanwhile, at the border, Romanians do what they can, bringing food, blankets, toys, offering car rides, a bed, a meal in their own home.

I scroll through the photos of a photographer friend, Mugur Varzariu. As I thought, he is there, at the border, too. I ask him to tell me about a moment, a face, a situation that struck him, that helped him to keep hope and trust in humanity alive.

He tells me about Anastasiia, who arrived with her mother and her child from Odessa at the border checkpoint of Isaccea, carrying a trolley and nothing else. Exhausted, she burst into tears when she realized she didn’t have her biometric passport with her. The frontier commander, a big man in a dark uniform, offered her a rose, which had somehow ended up there in the confusion, and then he let her through. From Isaccea, Anastasiia found a lift to Bucharest, where she is now hosted by the mother of a Romanian gendarme. .

Faced with so much violence, so much pain, when despair seems to overwhelm us, we must take a moment to think about the example of so many people, women and men, who in the cold of the long night our continent is going through, open the doors of their homes and keep burning a flame of hope, as small as it is precious.

This article was adapted from the original published in Italian on March 4, 2022 in the online magazine Mentinfuga.

All pictures ©Mugur Varzariu

Giuliana Arena

Bucharest, Romania

March 2022

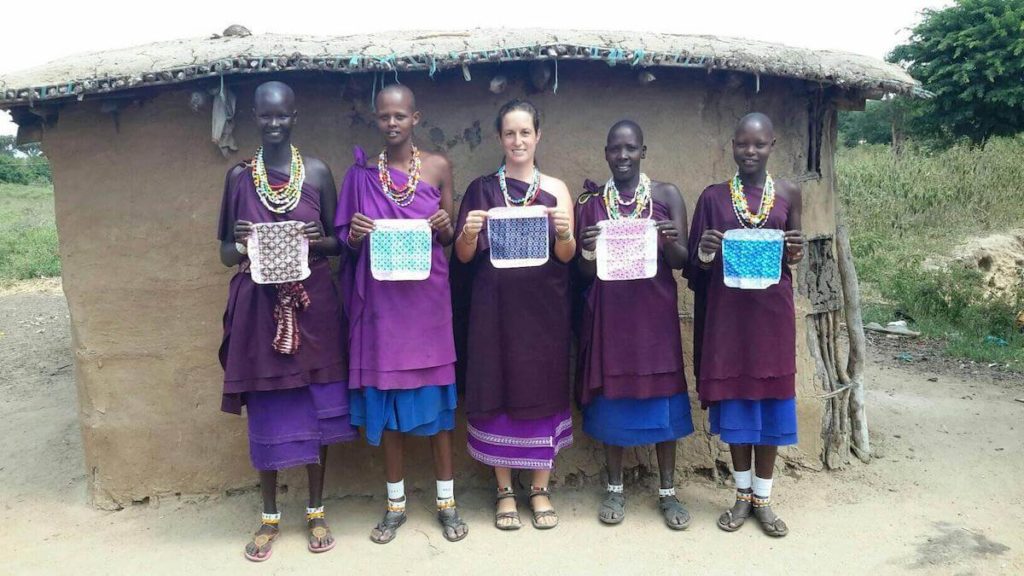

The biggest lesson I learned from living with the Maasai is that there are different ways of living. There is no ultimate truth and it’s very important to be openminded because my “right or wrong” is very different from the right or wrong of other cultures.

The biggest lesson I learned from living with the Maasai is that there are different ways of living. There is no ultimate truth and it’s very important to be openminded because my “right or wrong” is very different from the right or wrong of other cultures. I’ve a kid who is five and a half. I never worried too much about the values and culture I want to raise him with. That’s why I don’t even speak German to my child, I speak Maa, the indigenous language of his father and he knows a little bit of Swahili because he started school.

I’ve a kid who is five and a half. I never worried too much about the values and culture I want to raise him with. That’s why I don’t even speak German to my child, I speak Maa, the indigenous language of his father and he knows a little bit of Swahili because he started school.

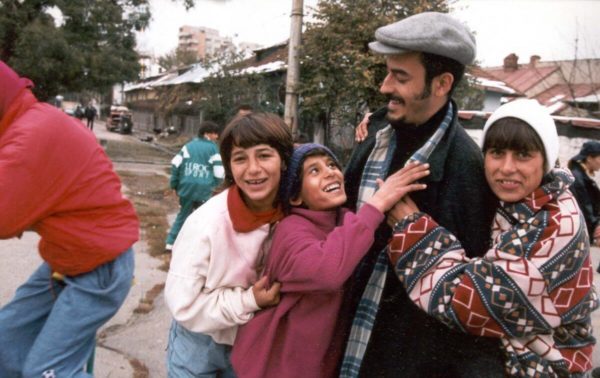

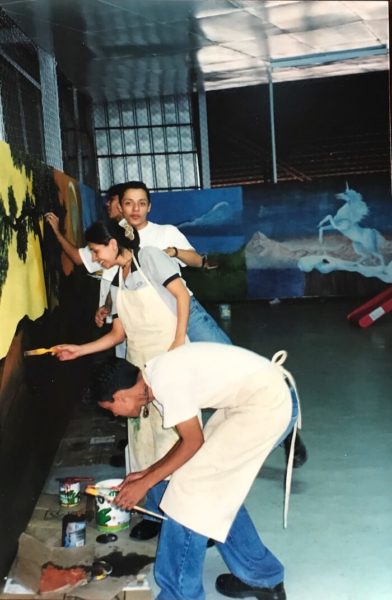

Franco discovered Parada in 1999 at an international conference where he presented some of the activities he had promoted with street children in Nepal. The following year, his NGO sent him to Bucharest for a feasibility study on Parada. Later, when UNICEF Romania approved Parada’s project, Franco was sent to follow the start-up phase for six months. He’s been in Romania ever since, and even though his role within Parada has changed over time, he’s still deeply engaged with the project that has marked his life so deeply.

Franco discovered Parada in 1999 at an international conference where he presented some of the activities he had promoted with street children in Nepal. The following year, his NGO sent him to Bucharest for a feasibility study on Parada. Later, when UNICEF Romania approved Parada’s project, Franco was sent to follow the start-up phase for six months. He’s been in Romania ever since, and even though his role within Parada has changed over time, he’s still deeply engaged with the project that has marked his life so deeply.

I asked Franco what is the biggest lesson he takes away from his experience. “I have learned that human relationship is the only valuable path in these situations. It is a matter of empathy, of emotions. There is just one methodology to use under these circumstances, and it is that of human relationship: if you get involved at this level, even if you make mistakes, you will always be there for the other. You must show that you are there. And this requires constancy. Forget what they told you at the university or when you were working in the social work field back home. These kids are not inferior beings that need our help. There is nothing more false than this. You are just a tool that gets involved to connect with that person, a person who is not inferior, but who just happens to live under different circumstances. We can hardly change our lives, how can we even think to change theirs?”

I asked Franco what is the biggest lesson he takes away from his experience. “I have learned that human relationship is the only valuable path in these situations. It is a matter of empathy, of emotions. There is just one methodology to use under these circumstances, and it is that of human relationship: if you get involved at this level, even if you make mistakes, you will always be there for the other. You must show that you are there. And this requires constancy. Forget what they told you at the university or when you were working in the social work field back home. These kids are not inferior beings that need our help. There is nothing more false than this. You are just a tool that gets involved to connect with that person, a person who is not inferior, but who just happens to live under different circumstances. We can hardly change our lives, how can we even think to change theirs?” Franco has no doubts: in terms of individual growth he has received much more from “his” boys than what he’s given them. They have been a real school of life, for him and all those who have worked with them.

Franco has no doubts: in terms of individual growth he has received much more from “his” boys than what he’s given them. They have been a real school of life, for him and all those who have worked with them.

At that time my work focused on extreme urban poverty and I had never experienced being stuck in a besieged neighbourhood during a civil war, resulting in hundreds of deaths – practically ignored by media (apart from the local ones); and I was physically allergic to ethnic fashion (I still am, a bit). My future wife looked at me in silence… and less than one year later I was beside her in a Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon. Since that moment I have done what the character of a song of Sergio Caputo (Italian songwriter, ndr) does: “I will follow you to show you something more, I’ll come with you should this be my work”.

At that time my work focused on extreme urban poverty and I had never experienced being stuck in a besieged neighbourhood during a civil war, resulting in hundreds of deaths – practically ignored by media (apart from the local ones); and I was physically allergic to ethnic fashion (I still am, a bit). My future wife looked at me in silence… and less than one year later I was beside her in a Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon. Since that moment I have done what the character of a song of Sergio Caputo (Italian songwriter, ndr) does: “I will follow you to show you something more, I’ll come with you should this be my work”. I have followed women on a three-hour trek to

I have followed women on a three-hour trek to  I have seen refugee camps with lean women and children as far as the eye can see, thousands of exhausted people, massed in camps between Kenya and Ethiopia, sitting on UNCHR rice bags. Being an aid worker is not a job for those who work for agencies that spend 70 or 80% of resources in staff (the aid workers I value and talk about are not only able to write projects and make ends meet; they dirty their hands – they risk). Aid workers do not think that the danger is always the fault of those who are kidnapped or attacked, or that you can always avoid danger. No, cooperation, in some places, is physically and psychologically dangerous work.

I have seen refugee camps with lean women and children as far as the eye can see, thousands of exhausted people, massed in camps between Kenya and Ethiopia, sitting on UNCHR rice bags. Being an aid worker is not a job for those who work for agencies that spend 70 or 80% of resources in staff (the aid workers I value and talk about are not only able to write projects and make ends meet; they dirty their hands – they risk). Aid workers do not think that the danger is always the fault of those who are kidnapped or attacked, or that you can always avoid danger. No, cooperation, in some places, is physically and psychologically dangerous work. Ani has no LinkedIn profile, no electronic CV, no website, and no blog. All of her working history is contained in those few worn-out papers – and when an employer leaves, she can only hope they will find her another job or be motivated enough to recommend her on expat websites and mailing lists. Her whole working future depends on the willingness of her employer to put energy in this search.

Ani has no LinkedIn profile, no electronic CV, no website, and no blog. All of her working history is contained in those few worn-out papers – and when an employer leaves, she can only hope they will find her another job or be motivated enough to recommend her on expat websites and mailing lists. Her whole working future depends on the willingness of her employer to put energy in this search.

Then, if they are available, I go to exhibitions and local markets to find art crafts: art, and especially photography, makes me understand the feelings and the way local people interpret reality, it tells me about their lives, it is a mirror of how they see and go through life events.

Then, if they are available, I go to exhibitions and local markets to find art crafts: art, and especially photography, makes me understand the feelings and the way local people interpret reality, it tells me about their lives, it is a mirror of how they see and go through life events.