In this article Claudia reflects on the differences between being an expat south or north of the world.

When I left Indonesia in May 2018, I knew I was not only saying goodbye to the country but to a whole period of my life, spent mostly in the southern part of the world. From then on, I knew that I would have to choose my destinations carefully. My third episode of Dengue fever had taken a serious toll on me: I had developed a severe thrombocytopenia, that would thereafter put me at high risk in any country where mosquito bites could potentially lead to malaria or yellow fever. Or where a blood transfusion, if needed, could put me at risk because the treatment of blood was unreliable.

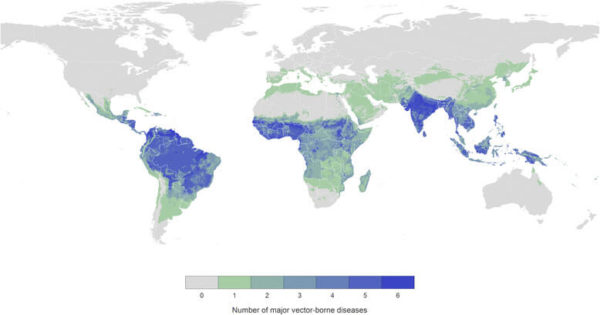

Look at this picture, which shows the global distribution of seven major vector-borne diseases (malaria, lymphatic filariasis, leishmaniasis, dengue, Japanese encephalitis, yellow fever and Chagas disease):

Out of the nine countries where I have lived since 1989, seven are marked in blue or dark green. When leaving Indonesia, it was clear to me that if I wanted to continue my life as an expat, I would have to head towards less exotic destinations.

And so, after a pause in my native Italy, I joined my husband in 2019, in Geneva, Switzerland, a huge novelty for me, since it was my first destination in Europe. When I moved there, I recalled those moments during the first years of managing Expatclic, when I got in touch with expats in European capitals or in big American cities. I remember always feeling a touch of envy for I had never lived as an expat in a Western or European culture. Now In Geneva, I wondered how such an experience in a place whose basic cultural assumptions I shared and where, presumably, I was largely understood, was going to take shape.

So there I was, trying to discern the benefits of being an expat in Geneva. And at a particular moment, they were many. Living in Geneva meant being physically close to my sons and to my mother. I planned to travel a lot. The strategic position of the city, in the heart of Europe, makes it possible to reach many destinations in little time and with no particular worries.

From a health standpoint, I enjoyed being relaxed. No mosquito bite would kill me, and in case of sudden hemorrhage, I would be promptly and safely treated. And in terms of communication, being a French speaker, understanding and being understood was an enormous relief, after not being able to communicate for years while living in countries where I did not speak the language because it would have taken me too long to acquire a reasonable proficiency.

Another aspect of living in Geneva that excited me was the abundant offer of movies, theatre shows, concerts and museums, and all the wonderful exhibitions I had so intensely missed during my latest period in Indonesia.

And then COVID changed all that. I lost my mother, travelling was prohibited, all places of culture were closed, and the fear of falling sick became as intense as it had been when I was in Jakarta because I knew the health structures were stretched to the limits of their capacities.

Even before COVID, though, I had started to realize that maybe all the positive points that marked my experience as an expat in the Western world were not enough to compensate for the loss of meaning that characterized my experiences of living abroad.

Even before COVID, though, I had started to realize that maybe all the positive points that marked my experience as an expat in the Western world were not enough to compensate for the loss of meaning that characterized my experiences of living abroad.

For me, it has always been about growing with people, about going through change after witnessing things that were so different from what I had known, and then coming out of the shock renewed and more open-minded. Furthermore, I believe that it is quite impossible to go through such life-changing moments if one does not immerse oneself in very different cultures and situations.

The most obvious disparity for me, however, is the unequal distribution of privilege. There is a huge difference between the state of mind of people who do not have to fight for their survival, and those who do. In my experiences abroad, I have mostly been in contact with the latter. Because of the nature of my husband’s work, the countries we were destined to had been hit by wars, natural disasters, famine, and poverty. These events shape people’s minds, life philosophy, and values in a totally different way from those who do not have to worry about a roof over their head, food on the table, their physical safety, and the health of their children.

I realized that repeated exposure to people whose whole life structure was built on uncertainty, and who did not have all the freedom and privileges we mostly enjoy in our Western world, slowly changed not only my way of seeing things, but the places where I find meaning in life.

Besides, throughout my life abroad I have been constantly impacted by what I call positive culture shocks. Having lived in cultures where things are seen and done quite differently from what I was brought up to consider as correct or proper, I have repeatedly been shaken in my most basic assumptions about life and how relationships must develop. Witnessing new ways and finding new meanings has become vital nourishment for me. It was only when I moved to Geneva that I slowly realized all this and started missing it.

Besides, throughout my life abroad I have been constantly impacted by what I call positive culture shocks. Having lived in cultures where things are seen and done quite differently from what I was brought up to consider as correct or proper, I have repeatedly been shaken in my most basic assumptions about life and how relationships must develop. Witnessing new ways and finding new meanings has become vital nourishment for me. It was only when I moved to Geneva that I slowly realized all this and started missing it.

But there is much more I miss. Having lived most of my life abroad in countries where the collective side of life is far more enhanced than it is in the West, I realized how much better I felt surrounded by a generally more human attitude towards life and relationships. Because it is when people are brought up in groups rather than in small, closed families that there is a greater sense of identity and belonging to the whole and not just to the self. Generally speaking, in this kind of culture, such as Indonesian or Palestinian, contact between people is warmer, more cheerful, more open to the other – and to diversity.

I honestly do not know what I miss more: the atmosphere of some far away cultures, or myself existing within cultures so far away from mine. What I do know is that I have to find new ways to still feel connected to the immense treasure that such extreme experiences have given me.

I bought Tayo’s book and read it immediately. Right from chapter one, I knew this would become one of the most important books I have read in my life. At chapter two, I felt like a better and richer person. At chapter three, I knew I had to talk to Tayo.

I bought Tayo’s book and read it immediately. Right from chapter one, I knew this would become one of the most important books I have read in my life. At chapter two, I felt like a better and richer person. At chapter three, I knew I had to talk to Tayo. Fortunately for us, Tayo chose writing, exploration, research, and storytelling as tools to get the answers he needed.

Fortunately for us, Tayo chose writing, exploration, research, and storytelling as tools to get the answers he needed.

I became a mom in 2012. I had been gone from Peru (my native country) since 2008. I

I became a mom in 2012. I had been gone from Peru (my native country) since 2008. I  Now I am back in Lima temporarily. I have been here for the last 3 years. How has becoming a mom in a different country affected my being a mom at home? Well, I definitively have a different outlook on things. I am usually the one with the different opinion. More than once I have been specifically asked what I think of certain situations because my opinion was expected to bring a different perspective.

Now I am back in Lima temporarily. I have been here for the last 3 years. How has becoming a mom in a different country affected my being a mom at home? Well, I definitively have a different outlook on things. I am usually the one with the different opinion. More than once I have been specifically asked what I think of certain situations because my opinion was expected to bring a different perspective. Now, how can I contribute to my new surroundings with my experience? I think that bringing a different perspective – especially to a “local” environment” is already a contribution. Showing people that there are other ways to do things is already a win. Being different, not just talking about how things are different somewhere else, is also a way to confront the status quo and bring some fresh air to the context. Raising a “citizen of the world” kind of kid is also a gift, a child that doesn’t necessarily comply with the local social norms tends to raise some eyebrows and I think that is also good.

Now, how can I contribute to my new surroundings with my experience? I think that bringing a different perspective – especially to a “local” environment” is already a contribution. Showing people that there are other ways to do things is already a win. Being different, not just talking about how things are different somewhere else, is also a way to confront the status quo and bring some fresh air to the context. Raising a “citizen of the world” kind of kid is also a gift, a child that doesn’t necessarily comply with the local social norms tends to raise some eyebrows and I think that is also good. Mariam Navaid Ottimofiore is a Pakistani born expat who grew up in Bahrain, New York City and Karachi. She has been living abroad for 17 years, with her husband and her two children. She has presently just left Dubai and moved to Ghana. I met her at the Families in Global Transition (FIGT) conference in The Hague, Netherlands in 2017 and was delighted when I realized that at the 2018 conference (which I unfortunately could not attend) she held a session to introduce the topic of The ‘Other’ Expats – Diverse Voices from Dubai; How Race, Class and Privilege Affect Our Mobility Experience. I talked to her on the phone about it over the summer and our conversation confirmed the impression I had after meeting Mariam: she is a very empathetic, highly motivated person, who believes in the power of our expat lives to change the world around us. Thank you Mariam for your time and best wishes for your next assignment!

Mariam Navaid Ottimofiore is a Pakistani born expat who grew up in Bahrain, New York City and Karachi. She has been living abroad for 17 years, with her husband and her two children. She has presently just left Dubai and moved to Ghana. I met her at the Families in Global Transition (FIGT) conference in The Hague, Netherlands in 2017 and was delighted when I realized that at the 2018 conference (which I unfortunately could not attend) she held a session to introduce the topic of The ‘Other’ Expats – Diverse Voices from Dubai; How Race, Class and Privilege Affect Our Mobility Experience. I talked to her on the phone about it over the summer and our conversation confirmed the impression I had after meeting Mariam: she is a very empathetic, highly motivated person, who believes in the power of our expat lives to change the world around us. Thank you Mariam for your time and best wishes for your next assignment!

It could have been an ordinary well organized expat playgroup, like many I used to go to with my children in the past and in other countries.

It could have been an ordinary well organized expat playgroup, like many I used to go to with my children in the past and in other countries. These women continued to be socially isolated and had little reason to leave the refugee shelter except to shop for food and clothing. Most of their time is spent indoors, caring for their young children without the aid of their own toys or care items, such as pushchairs/buggies and highchairs. We believed the playgroup concept would be a good way to reach out to these women and children. It also held promise of a way to pass on things like clothes, toys and baby-care items – things that are readily available from international families in our networks who are often on the move.

These women continued to be socially isolated and had little reason to leave the refugee shelter except to shop for food and clothing. Most of their time is spent indoors, caring for their young children without the aid of their own toys or care items, such as pushchairs/buggies and highchairs. We believed the playgroup concept would be a good way to reach out to these women and children. It also held promise of a way to pass on things like clothes, toys and baby-care items – things that are readily available from international families in our networks who are often on the move. This book takes us on a fascinating journey through human evolution, a journey covering ground that our collective sentiment, for the most part, has not yet explored. The discovery of mirror neurons – so-called empathy neurons – during the 1990s offers a completely different interpretation and is leading scientists from a wide range of disciplines to rethink the theories that characterized the age of reason. Today the cognitive sciences seem to recognize that the most profound human instinct is not the anticipation of pleasure, nor even the struggle for survival or the selfish fulfillment of our own needs, but rather the creation of social ties.

This book takes us on a fascinating journey through human evolution, a journey covering ground that our collective sentiment, for the most part, has not yet explored. The discovery of mirror neurons – so-called empathy neurons – during the 1990s offers a completely different interpretation and is leading scientists from a wide range of disciplines to rethink the theories that characterized the age of reason. Today the cognitive sciences seem to recognize that the most profound human instinct is not the anticipation of pleasure, nor even the struggle for survival or the selfish fulfillment of our own needs, but rather the creation of social ties. I am talking about people in a group, let’s say as in chamber music, where there is no conductor, but where music is created by the members of the group relating one to the other.

I am talking about people in a group, let’s say as in chamber music, where there is no conductor, but where music is created by the members of the group relating one to the other. I so much appreciate these comments because they are perfectly in line with the aims of our project, ‘What Expats Can Do’. The idea is to find ways to get closer to the cultures that host us, so that the unknown becomes more and more familiar and does not frighten us. We are convinced that music is a wonderful way to do it. In some situations it is also a great way to break down barriers and “universalize” feelings. You have played (and have led others to play) with people from many walks of life – would you say that music is a language that contributes to minimize conflicts?

I so much appreciate these comments because they are perfectly in line with the aims of our project, ‘What Expats Can Do’. The idea is to find ways to get closer to the cultures that host us, so that the unknown becomes more and more familiar and does not frighten us. We are convinced that music is a wonderful way to do it. In some situations it is also a great way to break down barriers and “universalize” feelings. You have played (and have led others to play) with people from many walks of life – would you say that music is a language that contributes to minimize conflicts?  My family is not rich. My mom works as a maid and my dad moves from one casual job to another. The motorbike is essential for my mom to reach work every day, for my dad to job-hunt, and for us to go to school. Every morning, when it’s time to leave the house, my sister and I argue:

My family is not rich. My mom works as a maid and my dad moves from one casual job to another. The motorbike is essential for my mom to reach work every day, for my dad to job-hunt, and for us to go to school. Every morning, when it’s time to leave the house, my sister and I argue: The trip is long. We leave early from our neighbourhood in the suburbs of Jakarta, a depressed area packed with makeshift homes where sewage flows in the open, and rats share space with humans. Hanging laundry and piles of garbage dot the area, until the first shops appear, taking a bit of the squalor away.

The trip is long. We leave early from our neighbourhood in the suburbs of Jakarta, a depressed area packed with makeshift homes where sewage flows in the open, and rats share space with humans. Hanging laundry and piles of garbage dot the area, until the first shops appear, taking a bit of the squalor away. Some traffic lights are more interesting than others because of the hawkers. It is fun to see new things coming up all the time – colourful feather dusters are my favourite, they come in bright blue, pink, yellow and green, and I would give an arm and a leg to be able to touch them and feel the softness of the feathers. At the beginning of the year, huge calendars are on sale, and after elections, the portrait of the president and vice president are at all traffic lights.

Some traffic lights are more interesting than others because of the hawkers. It is fun to see new things coming up all the time – colourful feather dusters are my favourite, they come in bright blue, pink, yellow and green, and I would give an arm and a leg to be able to touch them and feel the softness of the feathers. At the beginning of the year, huge calendars are on sale, and after elections, the portrait of the president and vice president are at all traffic lights. A few days later, at the same traffic light, her car was close to our motorbike again, her window open. She flashed me a huge smile and spoke to me. She was using my language, but I could not understand what she was saying. She said: “Saya dari Italia.” I had never heard that word, Italia, before. Plus, I was intimidated by how strange she looked, with her hair cut short and many different necklaces around her neck.

A few days later, at the same traffic light, her car was close to our motorbike again, her window open. She flashed me a huge smile and spoke to me. She was using my language, but I could not understand what she was saying. She said: “Saya dari Italia.” I had never heard that word, Italia, before. Plus, I was intimidated by how strange she looked, with her hair cut short and many different necklaces around her neck.