We are so happy to publish Luz Restrepo’s presentation to the Human Library of Expatclic. Her story and experiences are such an example of how we can become real advocates of what we strongly believe must be done to make this world a better place.

I was born in Colombia, and have lived in Australia since 2010. My family and I were forced to take the decision to move here because of the political situation in our home country. We had to decide between staying and risking our lives and the lives of our daughters, or moving to a safer place.

I was born in Colombia, and have lived in Australia since 2010. My family and I were forced to take the decision to move here because of the political situation in our home country. We had to decide between staying and risking our lives and the lives of our daughters, or moving to a safer place.

What I immediately felt put me in a position of disadvantage was that I spoke no English. And as many of you know, when we don’t speak the language, when we know no one, when we don’t know where we are, we need to start all over again. And starting again means that we must eat humble pie and learn again how to connect with the human and physical environment surrounding us. Certainly, as all moms will confirm, the wellbeing of our children is our top priority when we arrive in a new place. But as mothers and wives, while our husbands and children advance in the new country, we go backwards. We build our bubble of comfort within a close, known community, but we have no opportunities outside of it.

When I started to learn English, we did not have the resources to cover expensive courses. I started to study English in community centres in the suburbs of Melbourne. My classmates were all women that had settled in this country, three, five, some of them twenty years before. And while my English advanced well, their level remained the same. That made me wonder, “Why am I different?” I think one of the factors is education. When you are educated back home, you are more prone to absorb new things. You are also more curious: I was the only one in the class to ask for synonyms, antonyms, and spellings. What happens is also that many women that already live in a poverty circle in their home country come here and experience the additional barrier of the new language. And when they find themselves in the same class with other people who know how to navigate the education system, they are disadvantaged.

At that point I also realized that we learn the language by doing something meaningful in society, outside our homes. One such thing is a job, but how can you find a job when you are struggling to write the simplest things on paper? The solution I saw was to create a business together. I thought we should support each other. They had little English but lots of connections. We started to make handicrafts. We made crafts at home, and I looked for marketing opportunities in Melbourne. When we went to sell our handicrafts in the markets, we realized that our group of twenty-five multicultural women was very attractive to people. People loved to come and talk to us; they engaged themselves in our stories and bought our products. And by selling our products, we started enjoying the idea of having our own money, and our business minds began to develop.

Eight years ago I founded a charity, because no one wanted to lend me money for a proper business. We called it SisterWorks, Possibly it was my confidence as a businesswoman and the beauty of our mission that attracted more and more people to support migrant women’s economic empowerment. The organization grew rapidly. When the pandemic started, SisterWorks was supporting 900 women from more than 70 countries. We developed new ideas to create new products to sell on a big scale in supermarkets, other retail outlets, our own shops and online. SisterWorks fulfilled a need and UN Women came to us to find out how our business model was working. Our model of learning by doing and creating a sense of belonging and community support is now a worldwide pilot scheme with UN Women. As CEO, I oversaw the growth of the organisation from functioning on a zero-income, volunteer basis to one thriving with a staff of 20 and a $1.4M annual turnover by May 2020.

Two years ago, I realized that I am an entrepreneur, but my charity needed a manager – someone capable of developing systems and processes with the employees. I also realized that when long term unemployed migrant women find their first job in this country, they lose their voices, because they are not going to complain to their bosses. And I was the boss. They were doing all I said, but sometimes they disagreed with me. I didn’t know that, and when I found out, I realized I was taking their voices away, and I needed to give them their voices back.

In June 2020, in partnership with an amazing Australia businesswoman, Corinne Kemp, we founded Migrant Women in Business, an Australia-wide social enterprise that supports migrant and refugee women with nano or micro businesses to thrive and grow, and for their owners to become community leaders.

In June 2020, in partnership with an amazing Australia businesswoman, Corinne Kemp, we founded Migrant Women in Business, an Australia-wide social enterprise that supports migrant and refugee women with nano or micro businesses to thrive and grow, and for their owners to become community leaders.

Migrant Women in Business is a business, not a charity. The other thing I learned in this journey is that we migrants are not vulnerable people, and when we put ourselves within a charity contest, people see us as persons to help. But as new migrants, we don’t need charity – we just need to learn how to navigate in a new country. That’s why I created Migrant Women in Business as a business. I want to help migrant women to give a good structure to their business. I want to provide everything around a business: legal and financial care, product development, promotion, collaboration. The concept is to work together to learn from each other, and on the way, we support micro businesses of migrant women, which in turn generate work and welfare. This is the ecosystem of Migrant Women in Business in a nutshell.

Starting online in the middle of the pandemic, Corinne and I identified the need for networking activities and easily accessible digital tools designed for migrant women entrepreneurs who have varying levels of English literacy, technology skills, business opportunities and understanding of business culture in Australia. Migrant Women in Business is currently working for and with more than 90 businesswomen with migrant and refugee backgrounds, offering them commercial opportunities through our Made by Many Hands platform, and hands-on small business experts supported through Made by Many Minds.

33% of independent businesses in Australia are created by migrants, but only one out of ten is created by a migrant woman. We are the last in line. Also, there is little representation of migrant women in politics and business in Australia. I strongly believe that this is the time to have more women leaders in the world. We take care of the family, we are carers, we are leaders, and it’s time we were more represented in the public sphere. This is how we can create diversity.

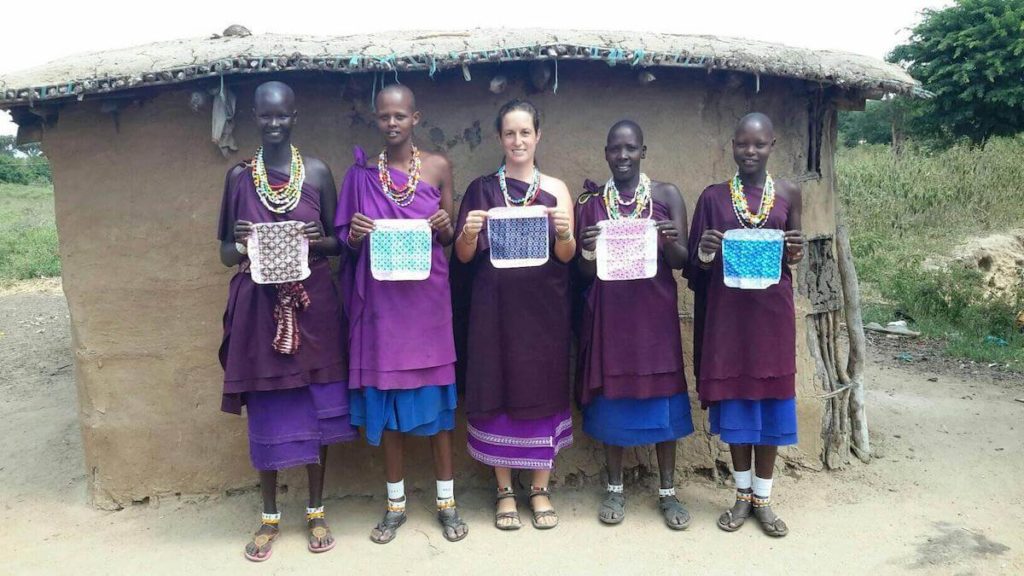

The biggest lesson I learned from living with the Maasai is that there are different ways of living. There is no ultimate truth and it’s very important to be openminded because my “right or wrong” is very different from the right or wrong of other cultures.

The biggest lesson I learned from living with the Maasai is that there are different ways of living. There is no ultimate truth and it’s very important to be openminded because my “right or wrong” is very different from the right or wrong of other cultures. I’ve a kid who is five and a half. I never worried too much about the values and culture I want to raise him with. That’s why I don’t even speak German to my child, I speak Maa, the indigenous language of his father and he knows a little bit of Swahili because he started school.

I’ve a kid who is five and a half. I never worried too much about the values and culture I want to raise him with. That’s why I don’t even speak German to my child, I speak Maa, the indigenous language of his father and he knows a little bit of Swahili because he started school.

Even before COVID, though, I had started to realize that maybe all the positive points that marked my experience as an expat in the Western world were not enough to compensate for the loss of meaning that characterized my experiences of living abroad.

Even before COVID, though, I had started to realize that maybe all the positive points that marked my experience as an expat in the Western world were not enough to compensate for the loss of meaning that characterized my experiences of living abroad. Besides, throughout my life abroad I have been constantly impacted by what I call positive culture shocks. Having lived in cultures where things are seen and done quite differently from what I was brought up to

Besides, throughout my life abroad I have been constantly impacted by what I call positive culture shocks. Having lived in cultures where things are seen and done quite differently from what I was brought up to

I bought Tayo’s book and read it immediately. Right from chapter one, I knew this would become one of the most important books I have read in my life. At chapter two, I felt like a better and richer person. At chapter three, I knew I had to talk to Tayo.

I bought Tayo’s book and read it immediately. Right from chapter one, I knew this would become one of the most important books I have read in my life. At chapter two, I felt like a better and richer person. At chapter three, I knew I had to talk to Tayo. Fortunately for us, Tayo chose writing, exploration, research, and storytelling as tools to get the answers he needed.

Fortunately for us, Tayo chose writing, exploration, research, and storytelling as tools to get the answers he needed.

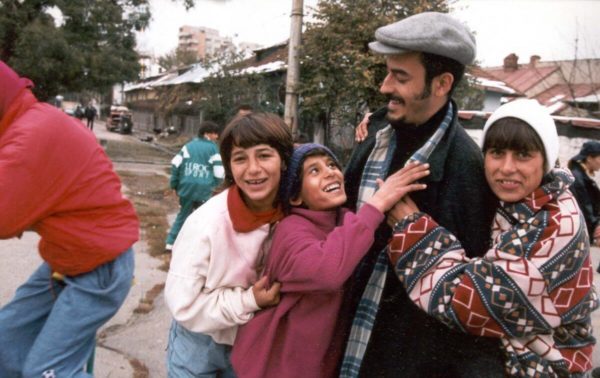

Franco discovered Parada in 1999 at an international conference where he presented some of the activities he had promoted with street children in Nepal. The following year, his NGO sent him to Bucharest for a feasibility study on Parada. Later, when UNICEF Romania approved Parada’s project, Franco was sent to follow the start-up phase for six months. He’s been in Romania ever since, and even though his role within Parada has changed over time, he’s still deeply engaged with the project that has marked his life so deeply.

Franco discovered Parada in 1999 at an international conference where he presented some of the activities he had promoted with street children in Nepal. The following year, his NGO sent him to Bucharest for a feasibility study on Parada. Later, when UNICEF Romania approved Parada’s project, Franco was sent to follow the start-up phase for six months. He’s been in Romania ever since, and even though his role within Parada has changed over time, he’s still deeply engaged with the project that has marked his life so deeply.

I asked Franco what is the biggest lesson he takes away from his experience. “I have learned that human relationship is the only valuable path in these situations. It is a matter of empathy, of emotions. There is just one methodology to use under these circumstances, and it is that of human relationship: if you get involved at this level, even if you make mistakes, you will always be there for the other. You must show that you are there. And this requires constancy. Forget what they told you at the university or when you were working in the social work field back home. These kids are not inferior beings that need our help. There is nothing more false than this. You are just a tool that gets involved to connect with that person, a person who is not inferior, but who just happens to live under different circumstances. We can hardly change our lives, how can we even think to change theirs?”

I asked Franco what is the biggest lesson he takes away from his experience. “I have learned that human relationship is the only valuable path in these situations. It is a matter of empathy, of emotions. There is just one methodology to use under these circumstances, and it is that of human relationship: if you get involved at this level, even if you make mistakes, you will always be there for the other. You must show that you are there. And this requires constancy. Forget what they told you at the university or when you were working in the social work field back home. These kids are not inferior beings that need our help. There is nothing more false than this. You are just a tool that gets involved to connect with that person, a person who is not inferior, but who just happens to live under different circumstances. We can hardly change our lives, how can we even think to change theirs?” Franco has no doubts: in terms of individual growth he has received much more from “his” boys than what he’s given them. They have been a real school of life, for him and all those who have worked with them.

Franco has no doubts: in terms of individual growth he has received much more from “his” boys than what he’s given them. They have been a real school of life, for him and all those who have worked with them.

Then, if they are available, I go to exhibitions and local markets to find art crafts: art, and especially photography, makes me understand the feelings and the way local people interpret reality, it tells me about their lives, it is a mirror of how they see and go through life events.

Then, if they are available, I go to exhibitions and local markets to find art crafts: art, and especially photography, makes me understand the feelings and the way local people interpret reality, it tells me about their lives, it is a mirror of how they see and go through life events.