We are grateful to Stephanie Fuchs for allowing us to transcribe part of her presentation to the Expatclic’s Human Library.

The biggest lesson I learned from living with the Maasai is that there are different ways of living. There is no ultimate truth and it’s very important to be openminded because my “right or wrong” is very different from the right or wrong of other cultures.

The biggest lesson I learned from living with the Maasai is that there are different ways of living. There is no ultimate truth and it’s very important to be openminded because my “right or wrong” is very different from the right or wrong of other cultures.

I come from Germany, and I’ve been living with the Maasai in Tanzania for more than ten years. I met my husband on an island of the coast of Zanzibar when he was working as a security guard to support his family. Stereotypes would want the Maasai to be an isolated group that lives far away from everything. In fact, they are already out into the big wide world, there are Maasai living in America, in Germany, wherever. They come in touch with us, white people, working in the tourism industry, while bravely holding on to their traditional way of life.

I find it difficult to define myself. I studied biology but now I live with the Maasai, I speak their tribal language, Swahili, I probably know more about the Maasai than someone who’s done a PhD on them, but I would never call myself an anthropologist, because this is a definition that I feel doesn’t fit. Another thing the Maasai taught me is that we have to stop to always want to put things into boxes. I can’t be put in a box because I’m a crazy German woman who went to live with an indigenous tribe in Tanzania and I left my culture behind, but I wouldn’t call myself a Maasai either, I don’t feel it’s my right because their upbringing is so much tougher than mine and I have many privileges they don’t have.

I think we must be much more fluid and accepting. This would help us understand things better, be more tolerant and broaden our horizons. I learnt that while we might find customs of some people very weird, Maasai might find it strange that we spend 100 dollars for a pair of jeans, a sum that feeds their family for a whole month.

We must listen to other people, take more time to understand without judging, not wanting to have a quick and easy picture of what other people are like. Judging is easy and doesn’t require any energy but understanding comes from wanting to love.

My story can show people that there are so many ways of living and I’m very happy whenever I let people have an insight into the world I’ve chosen to live in.

I left Germany when I was 19 years, 16 years ago, I have very little ties in Germany, my parents passed away before I came to Tanzania, I have just a sister and a brother in Germany. My dream was always to travel and to broaden my horizon, to meet different people and learn different things. Luckily I was able to do so.

I’ve a kid who is five and a half. I never worried too much about the values and culture I want to raise him with. That’s why I don’t even speak German to my child, I speak Maa, the indigenous language of his father and he knows a little bit of Swahili because he started school.

I’ve a kid who is five and a half. I never worried too much about the values and culture I want to raise him with. That’s why I don’t even speak German to my child, I speak Maa, the indigenous language of his father and he knows a little bit of Swahili because he started school.

The person that helped me the most when I had my child was my mother-in-law. I love her very much; she is an amazing person and she only speaks Maa. For the first three months we were living together, she helped a lot, holding the baby through the night, cooking and so on. For me it felt really wrong talking English to my child, a language that my mother-in-law does not understand. It would have been very disrespectful. So, I started speaking with my child the language of his father and of the people we live with.

Recently, I forced myself to speak English to him. I wanted to teach him one Western language, and English the most appropriate one, but if he is as good in languages as I am maybe one day I will also start speaking German to him.

It would be interesting to interview a few Maasai from different regions and ask them what it means to be Maasai today and how they look at their future. They’re an indigenous traditional tribe but they are also in touch with modernity. This is an interesting moment in their development and a challenging time. The issue with many Maasai is that they don’t even understand the value of what they have, their ancient wisdom and culture, their beautiful traditions.

There are, however, Maasai organisations fighting for their land and for the uphold of their ancient traditions. Some Maasai are very proud of being Maasai, but the younger generation is changing, they are having an education in the big cities and they are becoming more Westernise. They start seeing the negative sides of their culture and some are even ashamed of being Maasai. It’s very difficult for them to find their place in this modern world. They realise that the world is changing and that they need to change with it, but it’s not easy to find a balance between traditions and changes.

My husband is very proud of being Maasai, but it was still difficult for him to accept, for example, to marry a woman assigned to him by his father. He refused that, and caused a massive confrontation with his father, who was close to put a cross on him.

As I said, my parents passed away more than ten years ago. I’ve my sister coming here frequently visiting me and many friends too. The first couple of years my family and friends were shocked by my choice to merry a Maasai, but now they are totally happy because they see how happy I am, how much my life fulfills me.

Of course, I’m still a woman from Germany and there are certain things within the Maasai culture I find difficult to agree with, for example the status of women in Maasai society, but instead of disrespecting them for this or fighting with it, I do little things that maybe have a positive impact on the women here.

With my Western education, I also brought them a new understanding of climate change, of how important nature is, how they need to look after animals in different ways.

When I came here, I needed their help because I didn’t know how to fetch water, how to cut firewood, I didn’t know how to build a house, I didn’t know how to go in the bushes and find wild honey, I didn’t know which foods were edible and which were not. I was completely useless, and I felt always inferior to them in many ways. I still do to some extent, but I have also come to realise that I can use something from my Western education to help them deal with the challenges that they are facing.

In 2016 and 2017 we had a very bad dry season. In September the cattle started starving, there was no more grass. Several cows had babies and didn’t have a drop of milk for them, the baby cows started dying and we tried to keep the mamas alive, but they were so weak that when they lied down at night to sleep, they couldn’t get up anymore, they didn’t have the strength to get up, so we had to get up them. I saw all the world I loved falling apart, because the entire Maasai culture evolves around cattle. That’s why a few Maasai committed suicide: they couldn’t bear to see their cattle die of starvation. At that time I had my own struggles because my baby was not even a year old, but I started thinking.

I started researching on the Internet and I found a training centre in Kenya specifically designed for the Maasai. They teach them land management, environmental protection, and also new ways of herding their cattle, rotational grazing and so on. This centre is very expensive, so I started a crowdfunding campaign, and it was actually the reason why I opened my Instagram account: in order to do a successful crowdfunding campaign you have to be present on social media.

I didn’t expect so many people to follow my life and to think it was very cool and brave. They supported the campaign and made it a success.

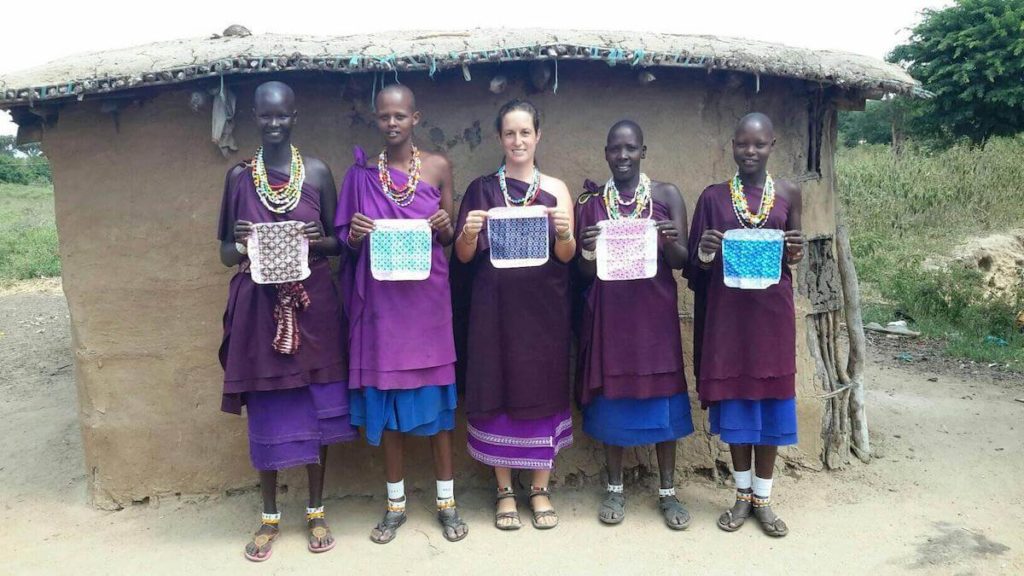

A lady following me from Australia was involved with making reusable day pads for women and she brought here some of them and women absolutely love them. It was completely out of my radar to assist the women with their period, I didn’t think it was a problem but, actually, it was. Then I decided to teach women how to make their own reusable pads. I have two of my sisters in law working with me with sewing and it’s going really well.

As for the relationship between the Maasai and the government of Tanzania: the government generally encourages them to leave their traditional way of life. Their life is based on land and all the land has been taken away from them for the sake of national parks, hunting concessions, housing and so on.

So, the Maasai are currently living between national parks and farms improving housing, and the situation is increasingly difficult because the population continues to increase. When they go to school they’re not allowed to wear their traditional clothes and their jewellery, they don’t speak their indigenous language. There are people who admire them for their way of life, for the way they hold on to their culture, for their looks and for their bravery, but there also many Tanzanians, especially those educated by Western standards, who look down on them.

Stephanie Fuchs

Human book at Expatclic Human Library 2021

@masai_story

All pictures ©StephanieFuchs

For another story from the Expatclic Human Library clic here.

At that time my work focused on extreme urban poverty and I had never experienced being stuck in a besieged neighbourhood during a civil war, resulting in hundreds of deaths – practically ignored by media (apart from the local ones); and I was physically allergic to ethnic fashion (I still am, a bit). My future wife looked at me in silence… and less than one year later I was beside her in a Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon. Since that moment I have done what the character of a song of Sergio Caputo (Italian songwriter, ndr) does: “I will follow you to show you something more, I’ll come with you should this be my work”.

At that time my work focused on extreme urban poverty and I had never experienced being stuck in a besieged neighbourhood during a civil war, resulting in hundreds of deaths – practically ignored by media (apart from the local ones); and I was physically allergic to ethnic fashion (I still am, a bit). My future wife looked at me in silence… and less than one year later I was beside her in a Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon. Since that moment I have done what the character of a song of Sergio Caputo (Italian songwriter, ndr) does: “I will follow you to show you something more, I’ll come with you should this be my work”. I have followed women on a three-hour trek to

I have followed women on a three-hour trek to  I have seen refugee camps with lean women and children as far as the eye can see, thousands of exhausted people, massed in camps between Kenya and Ethiopia, sitting on UNCHR rice bags. Being an aid worker is not a job for those who work for agencies that spend 70 or 80% of resources in staff (the aid workers I value and talk about are not only able to write projects and make ends meet; they dirty their hands – they risk). Aid workers do not think that the danger is always the fault of those who are kidnapped or attacked, or that you can always avoid danger. No, cooperation, in some places, is physically and psychologically dangerous work.

I have seen refugee camps with lean women and children as far as the eye can see, thousands of exhausted people, massed in camps between Kenya and Ethiopia, sitting on UNCHR rice bags. Being an aid worker is not a job for those who work for agencies that spend 70 or 80% of resources in staff (the aid workers I value and talk about are not only able to write projects and make ends meet; they dirty their hands – they risk). Aid workers do not think that the danger is always the fault of those who are kidnapped or attacked, or that you can always avoid danger. No, cooperation, in some places, is physically and psychologically dangerous work.