Living abroad offers us opportunities to be in contact with unfamiliar cultures and to listen to life stories far removed from ours. I believe that “telling” is one of our duties when we encounter stories of people who have no voice, stories that could slip by us silently. One of the most important tools of empathy is listening to others without prejudice.

Listening and telling is what Lucio Cascavilla, musician, writer and documentarist, did, while making his documentary The Years We Have Been Nowhere, which will be released in September, and which tells the stories of many deportees from Western countries. At the same time, Lucio was writing the graphic novel (or I should say graphic journal) which will be published in Italy as “Tre storie per non morire” (“Three stories of how not to die”). The book, illustrated by Mattia Vesco, Assia Ieradi and Riccardo Mattia and published by Morsi Editore, is set in Sierra Leone, a country where the author lived for two years and where he shot the documentary.

“Without dignity there is no freedom, without justice there is no dignity”: these words were spoken by Patrice Lumumba, who was Prime minister for a few months in 1960, and led the independence movement in the Democratic Reublic of the Congo from then until Mobutu’s coup in 1961. This is one of the many quotes that can be found in the book and aptly represents the idea on which it is based.

The book talks about departures, returns, and the impossibility of leaving a country, Sierra Leone, a country about which we know very little, and which deeply marked Lucio.

I would like to dwell on the distressing thought with which Valerio Nicolosi opens his preface, a thought that accompanies the reader all the way through, and that will hardly leave him even after the last page. It is the idea of going on an endless journey with only hope: facing weeks, months, maybe even years of fear, violence, and abuse, but resisting in the name of those hopes that weigh on you like the most precious luggage.

I would like to dwell on the distressing thought with which Valerio Nicolosi opens his preface, a thought that accompanies the reader all the way through, and that will hardly leave him even after the last page. It is the idea of going on an endless journey with only hope: facing weeks, months, maybe even years of fear, violence, and abuse, but resisting in the name of those hopes that weigh on you like the most precious luggage.

And then, in a flash, the police, perhaps even the police of that very country that embodied your dreams for the future, capture you and bring you back. In just a few hours you’re back to square one. Months of travel to get away, a few hours to come back. A return to a “home” that is no longer really home, because over there those who are forced to return are considered losers who did not make it. An anguish that takes your breath away.

The graphic novel tells three painful stories that Lucio Cascavilla has decided voice. They are set in Sierra Leone’s capital, Freetown.

There is the story of Abbas, brought back in chains to Freetown after a long journey to the United States; there is the story of Foday, who is only 27, and cannot leave because he is alone and sick, confined to a wheelchair, spending his days begging outside a hotel; and there is Regina, who returns after spending many years in Germany to escape from the massacres that have marked Sierra Leone, and is still facing endless difficulties.

Among the pages of “Three stories of how not to die” we also find the voice of our comfortable Western world. It accompanies all the stories in the background: it is the voice of the radio or television that distracts us with irrelevant issues, politicians’ promises, and popular songs.

There are many reflections that can arise from this book. Among them, the idea that “the destinies of people are connected, whether they live in China, Africa or Europe”: this is increasingly evident, but we tend to forget.

This is why we should be thankful to people who, while living abroad, make us aware of the realities they face.

Focusing on stories of individual people hidden behind the numbers that we read or hear in the news is essential.

Because if it is true that “What matters is not to know the world, but to change it”, as Frantz Fanon, a psychiatrist originally from Martinique and specialized in decolonization (quoted in the book), said, changing the world starts with changing each conscience, and awareness is the first and indispensable step towards this goal.

Giuliana Arena

Bucharest, Romania

March 2022

Often, when people think differently about a subject, they find it difficult to understand each other, and then, given presumptions on what they understand, things escalate to a fight.

Often, when people think differently about a subject, they find it difficult to understand each other, and then, given presumptions on what they understand, things escalate to a fight.

I bought Tayo’s book and read it immediately. Right from chapter one, I knew this would become one of the most important books I have read in my life. At chapter two, I felt like a better and richer person. At chapter three, I knew I had to talk to Tayo.

I bought Tayo’s book and read it immediately. Right from chapter one, I knew this would become one of the most important books I have read in my life. At chapter two, I felt like a better and richer person. At chapter three, I knew I had to talk to Tayo. Fortunately for us, Tayo chose writing, exploration, research, and storytelling as tools to get the answers he needed.

Fortunately for us, Tayo chose writing, exploration, research, and storytelling as tools to get the answers he needed.

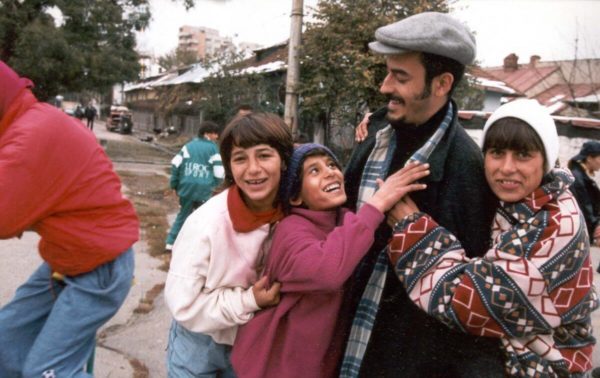

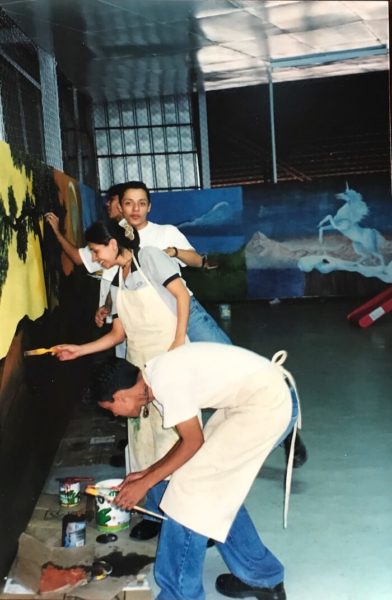

Franco discovered Parada in 1999 at an international conference where he presented some of the activities he had promoted with street children in Nepal. The following year, his NGO sent him to Bucharest for a feasibility study on Parada. Later, when UNICEF Romania approved Parada’s project, Franco was sent to follow the start-up phase for six months. He’s been in Romania ever since, and even though his role within Parada has changed over time, he’s still deeply engaged with the project that has marked his life so deeply.

Franco discovered Parada in 1999 at an international conference where he presented some of the activities he had promoted with street children in Nepal. The following year, his NGO sent him to Bucharest for a feasibility study on Parada. Later, when UNICEF Romania approved Parada’s project, Franco was sent to follow the start-up phase for six months. He’s been in Romania ever since, and even though his role within Parada has changed over time, he’s still deeply engaged with the project that has marked his life so deeply.

I asked Franco what is the biggest lesson he takes away from his experience. “I have learned that human relationship is the only valuable path in these situations. It is a matter of empathy, of emotions. There is just one methodology to use under these circumstances, and it is that of human relationship: if you get involved at this level, even if you make mistakes, you will always be there for the other. You must show that you are there. And this requires constancy. Forget what they told you at the university or when you were working in the social work field back home. These kids are not inferior beings that need our help. There is nothing more false than this. You are just a tool that gets involved to connect with that person, a person who is not inferior, but who just happens to live under different circumstances. We can hardly change our lives, how can we even think to change theirs?”

I asked Franco what is the biggest lesson he takes away from his experience. “I have learned that human relationship is the only valuable path in these situations. It is a matter of empathy, of emotions. There is just one methodology to use under these circumstances, and it is that of human relationship: if you get involved at this level, even if you make mistakes, you will always be there for the other. You must show that you are there. And this requires constancy. Forget what they told you at the university or when you were working in the social work field back home. These kids are not inferior beings that need our help. There is nothing more false than this. You are just a tool that gets involved to connect with that person, a person who is not inferior, but who just happens to live under different circumstances. We can hardly change our lives, how can we even think to change theirs?” Franco has no doubts: in terms of individual growth he has received much more from “his” boys than what he’s given them. They have been a real school of life, for him and all those who have worked with them.

Franco has no doubts: in terms of individual growth he has received much more from “his” boys than what he’s given them. They have been a real school of life, for him and all those who have worked with them.

Many sociologists agree that society is losing its ability to maintain community. More people feel disconnected, lonely, and hopeless: emotionally homeless.

Many sociologists agree that society is losing its ability to maintain community. More people feel disconnected, lonely, and hopeless: emotionally homeless. People have to actually go and find friends now, more often and possibly more frequently than before. For a long time, that was a task reserved more for TCKs, migrant and transient people, or displaced people… but more and more it’s a task for everyone, and many aren’t prepared for, let alone aware of the need to do so.

People have to actually go and find friends now, more often and possibly more frequently than before. For a long time, that was a task reserved more for TCKs, migrant and transient people, or displaced people… but more and more it’s a task for everyone, and many aren’t prepared for, let alone aware of the need to do so. At that time my work focused on extreme urban poverty and I had never experienced being stuck in a besieged neighbourhood during a civil war, resulting in hundreds of deaths – practically ignored by media (apart from the local ones); and I was physically allergic to ethnic fashion (I still am, a bit). My future wife looked at me in silence… and less than one year later I was beside her in a Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon. Since that moment I have done what the character of a song of Sergio Caputo (Italian songwriter, ndr) does: “I will follow you to show you something more, I’ll come with you should this be my work”.

At that time my work focused on extreme urban poverty and I had never experienced being stuck in a besieged neighbourhood during a civil war, resulting in hundreds of deaths – practically ignored by media (apart from the local ones); and I was physically allergic to ethnic fashion (I still am, a bit). My future wife looked at me in silence… and less than one year later I was beside her in a Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon. Since that moment I have done what the character of a song of Sergio Caputo (Italian songwriter, ndr) does: “I will follow you to show you something more, I’ll come with you should this be my work”. I have followed women on a three-hour trek to

I have followed women on a three-hour trek to  I have seen refugee camps with lean women and children as far as the eye can see, thousands of exhausted people, massed in camps between Kenya and Ethiopia, sitting on UNCHR rice bags. Being an aid worker is not a job for those who work for agencies that spend 70 or 80% of resources in staff (the aid workers I value and talk about are not only able to write projects and make ends meet; they dirty their hands – they risk). Aid workers do not think that the danger is always the fault of those who are kidnapped or attacked, or that you can always avoid danger. No, cooperation, in some places, is physically and psychologically dangerous work.

I have seen refugee camps with lean women and children as far as the eye can see, thousands of exhausted people, massed in camps between Kenya and Ethiopia, sitting on UNCHR rice bags. Being an aid worker is not a job for those who work for agencies that spend 70 or 80% of resources in staff (the aid workers I value and talk about are not only able to write projects and make ends meet; they dirty their hands – they risk). Aid workers do not think that the danger is always the fault of those who are kidnapped or attacked, or that you can always avoid danger. No, cooperation, in some places, is physically and psychologically dangerous work. In

In