I recently returned to Italy, my home country, while waiting for my next destination abroad. What I have found is a terrible reality in which the official narrative is based on racism, discrimination, and prejudice. I have been wondering what I, as an expat, can do to contribute to counteract all of this.

“Don’t you agree? You put a banana in her hand, set her on a branch, and you realize they are all monkeys”.

“They”, I gathered, were dark-skinned people.

This comment came from an exchange I overheard between a fitness instructor and his colleagues at a gym where I was doing some physiotherapy, last August. The instructor had barely finished a brief conversation with a dark-skinned lady before launching into this bigoted discourse.

I have come back to Italy to find a country torn by discrimination, mistrust, and a lack of solid values.

Racist and homophobic attacks of all sorts have been on the increase in the last years, but never before had I experienced such a recurrence in discriminatory acts in our daily lives.

From North to South, there has been an increase in physical attacks on migrants (some have been killed), verbal abuse, mocking, discriminatory measures to avoid employing foreigners, deny them housing, or even excluding them from school canteens.

Like all those in Italy at the moment who feel disgusted with this climate of hatred and violence, I have been wondering what can be done to counteract the terrible atmosphere that must be so frightening and intimidating to the many human beings who have come to my country in search of opportunities; and who, in many cases, have actually greatly contributed to the Italian economic growth.

In particular, because I have been an expat for more than half of my life, I feel it is my duty to find a way to dismantle the official narrative that painfully contradicts one of the most ancient and deeply rooted Italian values: hospitality.

Photo Credit Claudia Landini

I have been welcomed in so many countries in my life. I have never ever felt discriminated against or badly treated because of my background, provenance, skin colour, or for my role in those countries.

The openness that people of my host countries have repeatedly shown has allowed me to relate to them at a deep level, and to touch the commonalities each individual shares in life, and build on them.

In sharing simple daily routines with the people who welcomed me, I have felt accepted – and this has allowed me to destroy mental barriers that the fear of what is different often builds in our minds.

This is exactly what is happening in Italy now: some of our politicians are playing with the fear of the foreigner; a fear which many who have not had the chance to get in touch with diversity feel – and politicians build on it. They create a wall between “us” and “them”, and reinforce this gap by feeding stories of dishonesty, criminality, and profiting at the expense of “our” goods and capital.

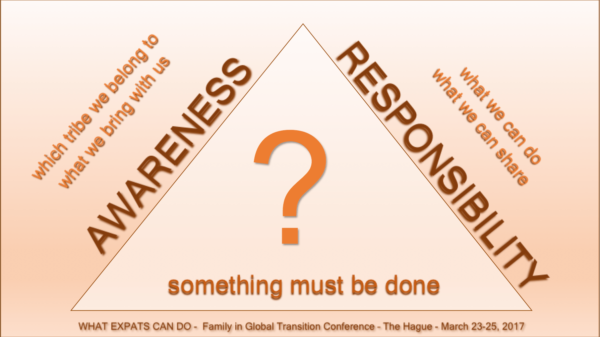

How we go about destroying this gap has been a desperate focus since my return. As Cristina says in her article about the power of our stories, I know I have the responsibility to share my experience with my countrymen who have not set foot outside of their borders and are more easily swayed by racist narratives.

On one side, I am aware that I have to find a way to explain that by living abroad, I have discovered how much all humans have in common. Deep down, we all want the same for our lives: dignity, health, and a beautiful life for our children.

I also discovered, though, that a wide portion of the world population struggle to achieve this. Some live in conditions that our countrymen cannot even imagine. And I know that if I manage to shift the focus of the narrative from what is happening in Italy to what is happening in the lands where most migrants come from, I can hopefully help change some minds – or at the very least shake some of the arrogant foundations of bigotry.

all rights reserved © Cristina Baldan

Ultimately, if there is one thing I am absolutely sure of, it is that I deeply appreciate the need and drive for migrants to desperately seek hope for a better life. I understand this because I have seen what happens outside our borders; and I think about what I would do in their shoes.

This is the “difference” we as expats can develop within ourselves: having witnessed how the other half on the planet lives, we can advocate for a warmer, more welcoming, and humane approach to these people’s realities. And this, I believe, is not just simply a choice, it’s our duty in these troubled times.

And I realize that when I start to tell my story, people become intrigued by my life.

And I realize that when I start to tell my story, people become intrigued by my life. Passionate about themes like injustice, racism, discrimination and violence, Cinzia lets herself be guided by her emotions when choosing the stories to document. “Once I discover something I believe has to be denounced, I work to gain trust in the people I want to photograph. I live with them, talk to them. This allows me to see their lives from the inside, and give the right angle to my photos”.

Passionate about themes like injustice, racism, discrimination and violence, Cinzia lets herself be guided by her emotions when choosing the stories to document. “Once I discover something I believe has to be denounced, I work to gain trust in the people I want to photograph. I live with them, talk to them. This allows me to see their lives from the inside, and give the right angle to my photos”.

Ani has no LinkedIn profile, no electronic CV, no website, and no blog. All of her working history is contained in those few worn-out papers – and when an employer leaves, she can only hope they will find her another job or be motivated enough to recommend her on expat websites and mailing lists. Her whole working future depends on the willingness of her employer to put energy in this search.

Ani has no LinkedIn profile, no electronic CV, no website, and no blog. All of her working history is contained in those few worn-out papers – and when an employer leaves, she can only hope they will find her another job or be motivated enough to recommend her on expat websites and mailing lists. Her whole working future depends on the willingness of her employer to put energy in this search.

Then, if they are available, I go to exhibitions and local markets to find art crafts: art, and especially photography, makes me understand the feelings and the way local people interpret reality, it tells me about their lives, it is a mirror of how they see and go through life events.

Then, if they are available, I go to exhibitions and local markets to find art crafts: art, and especially photography, makes me understand the feelings and the way local people interpret reality, it tells me about their lives, it is a mirror of how they see and go through life events.

Teachers are individuals, with different beliefs and experiences, who give their time to this project for their own reasons, however, “in the end they are all driven by the same desire to give”. This reminds us of our

Teachers are individuals, with different beliefs and experiences, who give their time to this project for their own reasons, however, “in the end they are all driven by the same desire to give”. This reminds us of our

Our school is based on a kind of freedom which is unthinkable in institutional structures, the freedom that comes from a direct personal relationship, one to one or in very small groups, made possible by the many people that are willing to teach for free: both students and teachers are volunteers. There are no classrooms, no marks. The only grade book used is to describe the work being done. We register attendance, not absence. We write down names and activities of the students, to allow every teacher to follow the student’s progress. The only style is the contact, the relationship between student and teacher, who sit side by side and “study” each other reciprocally.

Our school is based on a kind of freedom which is unthinkable in institutional structures, the freedom that comes from a direct personal relationship, one to one or in very small groups, made possible by the many people that are willing to teach for free: both students and teachers are volunteers. There are no classrooms, no marks. The only grade book used is to describe the work being done. We register attendance, not absence. We write down names and activities of the students, to allow every teacher to follow the student’s progress. The only style is the contact, the relationship between student and teacher, who sit side by side and “study” each other reciprocally.