An expat survey.

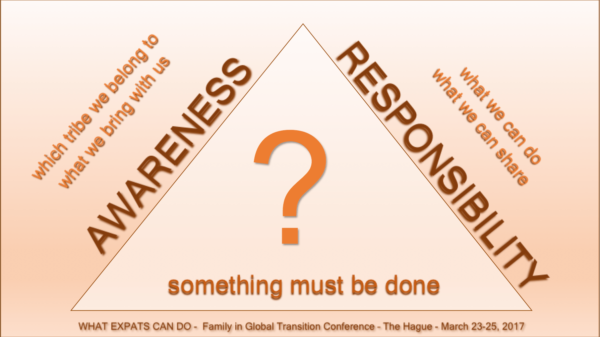

In my experience, I’ve realized that most expats are not aware of the enormous potential they have. Nor are they aware of the skills they’ve gained from this kind of life.

I suspect the reason is probably lying behind the psychological challenges and fatigue they are obliged to overcome every time they face a new assignment. When you start from the beginning over and over again, often by facing challenges that you would never expect (some very hard), you develop the belief that you are not an expert – you instinctively know how much you still have to learn every single time you approach a new country and a new culture.

However, I firmly believe that expats are an incredibly positive source of energy and of great value to current society: I have seen with my own eyes what they are capable of, and I am determined to help them to become aware of this… But how?

The Survey

The Survey

I decided to start by running an experiment. I enlisted the most qualified people I know in this field: the editing team of Expatclic.com.

The group of 7 women who answered my questions had all moved abroad as adults and had collectively lived outside their passport country for a total of 131 years, with an average of 18.7 years per person.

They lived as resident of a total of 31 countries (4.4 countries on average for each person) and they visited an additional total of 197 countries (28 on average for each person). All of this with accompanying children – some born abroad, some not.

Even knowing about the experiences of my colleagues, those numbers were still a surprise to me, and I think they constitute a solid group as far as interviewees.

Flexibility / Open-mindedness / Ability to network

The answers to my question about how much the expat lifestyle had changed the interviewees contained many similarities. Gaining the ability to be flexible and to adapt to changes – in situations as well as in relationships with unknown people – was probably the most frequent common theme. There was clearly a lot of self-awareness, and interviewees seem to have gained an open mind towards new cultures, to new ways of “doing things”. Furthermore, common to all the answers was the acquired ability to know how to better deal with people and how to build a network of human relationships in a foreign environment.

The most difficult challenge has been…

Loneliness, isolation, loss of identity, a sense of not-belonging, being forced out of a comfort zone, and feeling uncomfortable in a culture far from your own one. These are the strongest challenges these women reported having to face during their life abroad.

This result may not be surprising to you, but it is for me because I know that among these women there are some who have lived in really difficult countries and have faced some extreme challenges in terms of securities issues, discomfort, lack of basic services (like clean water), war danger, etc… It is surprising to me that those challenges weren’t listed as the most difficult ones.

Instead, challenges that threaten personal identity, our sense of belonging, and the possibility to have meaningful human relationships have been the most difficult part of the life abroad for these women.

Which of your personal resources was most useful in facing cultural shocks?

The women in this group are all happy with their experience overall. Despite the difficulties and hard times, they are still satisfied with the choices made, in fact, they offer their time and energy to help other expat women. Expatriation, however, is not always as successful as it was for them. So, I was curious to understand if there was a common starting point, a personal resource that helped them to overcome their challenges.

And indeed, I found some common skills in their answers:

- Positivity, sense of humor, meeting others with a smile

- Being adventurous

- Flexibility

- Empathy

- No judgment attitude, modesty

- Respect

- Above all curiosity: never being tired of learning about how other people live and understand life.

- Determination

The impact of expat life on human relationships with strangers and with familiar people

In all the contexts of human relationships (family, children, friends, colleagues, strangers, etc…), there is a common characteristic among these women: there is more desire for and attention given to the quality of the relationships. The expat life brings some peculiar and specific teachings in regards to how select your friends, how to educate your children, how to evaluate other people’s behavior, and how to relate to it.

By living abroad, you see and come into contact with other realities. You discover that things can be done in a different way and children can be raised and educated in different and unexpected ways, and the results can be as good as your own traditions. This develops an attitude of being open to learn from other cultures, to develop a feeling of freedom and wisdom in picking up and adopting what you evaluate may be good for you too. Most of the women interviewed think they would have been totally different mothers if they had raised their children in their home countries.

By living abroad, you see and come into contact with other realities. You discover that things can be done in a different way and children can be raised and educated in different and unexpected ways, and the results can be as good as your own traditions. This develops an attitude of being open to learn from other cultures, to develop a feeling of freedom and wisdom in picking up and adopting what you evaluate may be good for you too. Most of the women interviewed think they would have been totally different mothers if they had raised their children in their home countries.

The expat life also teaches you how to face adversity: the wide amount of difficulties an expat family experiences provide the training ground to learn how to screen out troubles, to identify the real priorities in life, and to become effective problem solvers. Most of the time you are alone to face your adversities without the support of good friends or family members. The reality is that you simply don’t have the time and/or the energy to make things complicated, and so become skilled in quickly finding workable solutions.

These women all see themselves as much stronger and resilient. They have acclimated to adversities in such a way that they face them when the time comes and fix them. This stands true despite things you would never plan for in a normal life like wars, serious illness, grief, criminality, and so on.

In addition to those hurdles, there is the learning about what is happening around you.

“Moving to different places, with different cultures, we necessarily learn, I believe, about the politics of the countries in which we live, of the neighbouring countries, of global issues, and of our country of origin. This, together with the capacity of understanding cultural differences, gives us the tools to be able to read and understand what is happening around us in a much better way”.

“Moving to different places, with different cultures, we necessarily learn, I believe, about the politics of the countries in which we live, of the neighbouring countries, of global issues, and of our country of origin. This, together with the capacity of understanding cultural differences, gives us the tools to be able to read and understand what is happening around us in a much better way”.

This sentence summarized the gift of being an expat in the best way possible. The expat life brings the gift of a special “lens” to see the world. This lens comes from having experienced living life in another country (or countries) first-hand. The ability to evaluate people and situations by automatically applying self-awareness and trying to avoid bias and judgment is one of the most common and valuable consequent skills.

Based on responses from these women who are currently working, I would also like to address some benefits of the expat experience that impact relationships in the professional environment:

- Knowing what to prioritize and when, and the ability to evaluate and solve problems

- Being able to analyze and quickly understand an unknown situation or environment

- Being able to adapt and work in an unfamiliar environment

- Constantly applying an attitude of self-reassessment to find solutions that may work

- Being able to relate and work with people coming from different cultures

- Being available to continually start from scratch and think about the future with an “out-of-the-box” attitude

Are there any Human Resource specialists reading right now? Would you agree that the list above encompasses some of the most wanted skills in a professional environment those days?

Unfortunately, it is very hard for a woman to have this kind of experience properly expressed in a resume (but this is a good topic for another article).

Change of life goals and self-awareness

When you choose this kind of life, you accept the unpredictable. Some are aware of this reality, but most are not. I asked the question: “Has the expat life changed your life goals and inspired you to do something totally different from your initial plan or dream?”. This is certainly a query worth an in-depth analysis.

What I first noticed in their answers was that when the expat life began in an early stage of their life, the goals didn’t change too much. For the ones who left a career, a job or a university degree in the home country, the change was in some way mandatory: all of them had to change perspective and adapt to new realities.

I wish I could have continued working and reaching my goals as a woman in the fields of finance.

I was a lawyer and I am a coach and facilitator now!

I wanted to be a scientist, now I’m considering becoming a teacher.

The ability to reinvent themselves to face a new situation is common, but it also brings a certain measure of suffering.

The last question

… if you could put three values or skills you gained in the expat life in a time capsule for your descendants which they could use in their own life, what would you choose?

- Flexibility and adaptability to new situations and to changes

- Curiosity of the world, for the people – Respect for others – Sense of adventure

- Ability to learn from your mistakes and don’t be ashamed to make them, they are part of our life

- Optimism – Empathy – Tolerance

- Ability to accept life events, the loss, the loneliness, the hard times

- Courage to keep going in front of adversities

- Gratitude and appreciation for what you have

- Knowledge – Sense of justice – Capacity of relativize

I don’t think I need to add any comment to this.

Conclusion

My research is not complete: this survey was just a first experiment. I want to dig more into the expats’ personal characteristics. There is still a lot to discover and to speak about.

I want to conclude this reflection with one last point and a question for you.

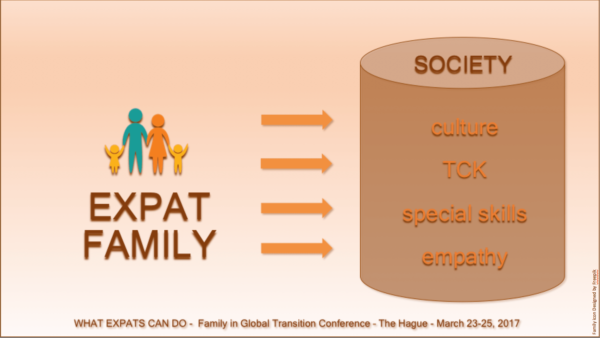

While I was reviewing their answers, I constantly found myself thinking about the richness these women can offer to society: not only as individuals but also as a group with their collective life experience.

That being said, I invite you to think and ask yourself:

What would the entire expat community be able to offer society if their experience is considered a whole?

If this reflection moved something in you, please share it with us! You can do this privately or through our Facebook page. All feedback helps us to improve this research and is evaluated with deep appreciation.

Many thanks to my interviewees, the Women behind Expatclic: you are simply and incredibly amazing!

Cristina Baldan

April 2019

All photos ©Expatclic

At that time my work focused on extreme urban poverty and I had never experienced being stuck in a besieged neighbourhood during a civil war, resulting in hundreds of deaths – practically ignored by media (apart from the local ones); and I was physically allergic to ethnic fashion (I still am, a bit). My future wife looked at me in silence… and less than one year later I was beside her in a Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon. Since that moment I have done what the character of a song of Sergio Caputo (Italian songwriter, ndr) does: “I will follow you to show you something more, I’ll come with you should this be my work”.

At that time my work focused on extreme urban poverty and I had never experienced being stuck in a besieged neighbourhood during a civil war, resulting in hundreds of deaths – practically ignored by media (apart from the local ones); and I was physically allergic to ethnic fashion (I still am, a bit). My future wife looked at me in silence… and less than one year later I was beside her in a Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon. Since that moment I have done what the character of a song of Sergio Caputo (Italian songwriter, ndr) does: “I will follow you to show you something more, I’ll come with you should this be my work”. I have followed women on a three-hour trek to

I have followed women on a three-hour trek to  I have seen refugee camps with lean women and children as far as the eye can see, thousands of exhausted people, massed in camps between Kenya and Ethiopia, sitting on UNCHR rice bags. Being an aid worker is not a job for those who work for agencies that spend 70 or 80% of resources in staff (the aid workers I value and talk about are not only able to write projects and make ends meet; they dirty their hands – they risk). Aid workers do not think that the danger is always the fault of those who are kidnapped or attacked, or that you can always avoid danger. No, cooperation, in some places, is physically and psychologically dangerous work.

I have seen refugee camps with lean women and children as far as the eye can see, thousands of exhausted people, massed in camps between Kenya and Ethiopia, sitting on UNCHR rice bags. Being an aid worker is not a job for those who work for agencies that spend 70 or 80% of resources in staff (the aid workers I value and talk about are not only able to write projects and make ends meet; they dirty their hands – they risk). Aid workers do not think that the danger is always the fault of those who are kidnapped or attacked, or that you can always avoid danger. No, cooperation, in some places, is physically and psychologically dangerous work. Mariam Navaid Ottimofiore is a Pakistani born expat who grew up in Bahrain, New York City and Karachi. She has been living abroad for 17 years, with her husband and her two children. She has presently just left Dubai and moved to Ghana. I met her at the Families in Global Transition (FIGT) conference in The Hague, Netherlands in 2017 and was delighted when I realized that at the 2018 conference (which I unfortunately could not attend) she held a session to introduce the topic of The ‘Other’ Expats – Diverse Voices from Dubai; How Race, Class and Privilege Affect Our Mobility Experience. I talked to her on the phone about it over the summer and our conversation confirmed the impression I had after meeting Mariam: she is a very empathetic, highly motivated person, who believes in the power of our expat lives to change the world around us. Thank you Mariam for your time and best wishes for your next assignment!

Mariam Navaid Ottimofiore is a Pakistani born expat who grew up in Bahrain, New York City and Karachi. She has been living abroad for 17 years, with her husband and her two children. She has presently just left Dubai and moved to Ghana. I met her at the Families in Global Transition (FIGT) conference in The Hague, Netherlands in 2017 and was delighted when I realized that at the 2018 conference (which I unfortunately could not attend) she held a session to introduce the topic of The ‘Other’ Expats – Diverse Voices from Dubai; How Race, Class and Privilege Affect Our Mobility Experience. I talked to her on the phone about it over the summer and our conversation confirmed the impression I had after meeting Mariam: she is a very empathetic, highly motivated person, who believes in the power of our expat lives to change the world around us. Thank you Mariam for your time and best wishes for your next assignment!